Holland, and its people

|

| Holland |

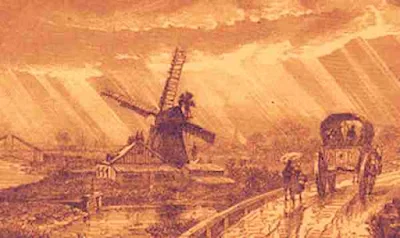

Those broken and compressed coasts, those deep bays, those great rivers that, losing the aspect of rivers, seem to bring new seas to the sea; and that sea, which, changing itself into rivers, penetrates the land and breaks it into archipelagoes j the lakes, the vast morasses, the canals crossing and recrossing each other, all combine to give the idea of a country that may at any moment disintegrate and disappear. Seals and beavers would seem to be its rightful inhabitants; but since there are men bold enough to live in it, they surely cannot ever sleep in peace.

These were my thoughts as I looked for the first time at a map of Holland, and experienced a desire to know something about the formation of so strange a country; and as that which I learned induced me to write this book, I put it down here, with the hope that it may induce others to read it. What sort of a country Holland is, has been told by many in few words. Napoleon said that it was an alluvion of French rivers, — the Rhine, the Scheldt, and the Meuse, — and with this pretext, he added it to the empire. One writer has defined it as a sort of transition between land and sea. Another, as an immense crust of earth floating on the water. Others, an annex of the old continent, the China of Europe, the end of the earth and the beginning of the ocean, a measureless raft of mud and sand; and Phillip II. called it the country nearest to hell.

But they all agreed upon one point, and all expressed it in the same words: — Holland is a conquest made by man over the sea — it is an artificial country — the Hol- landers made it — it exists because the Hollanders preserve it — it will vanish whenever the Hollanders shall abandon it. To comprehend this truth, we must imagine Holland as it was when first inhabited by the first German tribes that wandered away in search of a country. It was almost uninhabitable. There were vast tempestuous lakes, like seas, touching one another; morass beside morass j one tract covered with brushwood after another; immense forests of pines, oaks, and alders, traversed by herds of wild horses, and so thick were these forests that tradition says one could travel leagues passing from tree to tree without ever putting foot to the ground. The deep bays and gulfs carried into the heart of the country the fury of the northern tempests. Some provinces disappeared once every year under the waters of the sea and were nothing but muddy tracts, neither land nor water, where it was impossible either to walk or to sail.

the inhabitants of Flemish Zealand, rather than give it up to the Spaniards, cut their djd^es, let in the sea, and destroying in one day the labor of four centuries, it became once more the gulf of the middle ages. The war of independence over, the work of reformation was again commenced, and in three hundred years Flemish Zealand again emerged from the waters and was restored to the continent, like a daughter that had been dead and was alive again. Flemish Zealand, divided from Belgian Flanders by a double political and religious barrier, and separated from Holland by the Scheldt, preserves its customs and its faith as they were in the sixteenth century.

The traditions of the war with Spain are as speaking and vivid as any event of the day. The soil is fertile, the inhabitants enjoy a more than ordinary prosperity, they have schools and printing-presses, their manners are severe and simple, and they live peaceably on their fragment of country, rising from the sea but yesterday, until the day when the sea shall once more claim it for its third burial. A Belgian fellow-passenger, who gave me this information, called my attention to the fact that the inhabitants of Flemish Zealand, when they inundated their country and rose against the Spanish domination, were still Catholics; consequently, the strange circumstance occurred that while they went down into the waters good Catholics, they rose to the surface Protestants. To my great amazement, the ship, instead of continuing to descend the Scheldt and skirting the island of Zuid- Beveland, when it reached a certain point, entered a narrow canal which cuts that island into two parts and joins the two brandies of the river which are made by the island itself. It was the first Dutch canal that I had seen^ and the impression was a new one. It is bordered by two lofty dykes which hide the country; the ship glided along as if it were in ambush and meant to rnsh out at the other end to somebody's confusion, and as there was not a boat on the canal nor a living being on the banks^ the silence and solitude gave a still more piratical air to the proceeding.

Download 22 MB PDF ebook